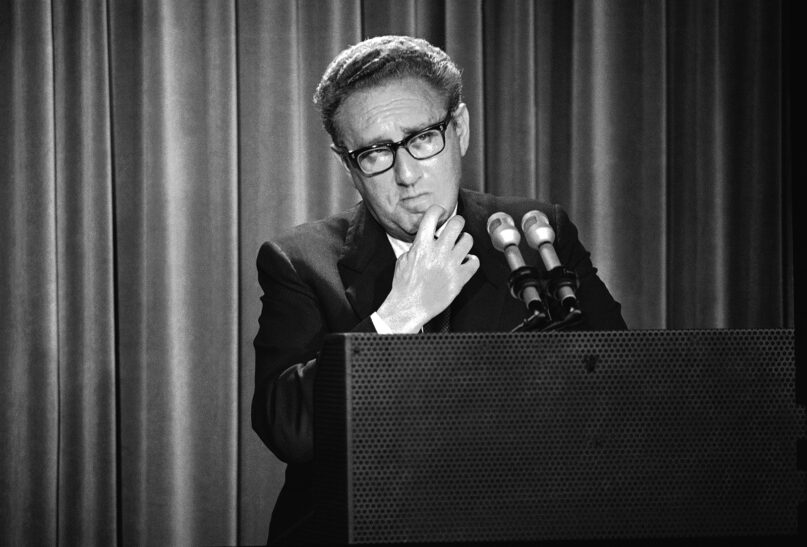

(RNS) — In the myriad reflections about Henry Kissinger’s legacy in the days after his death, much has been written about how realpolitik turned human rights into a transactional affair.

But much of what has been written or said about Kissinger in recent days still does not capture his enabling of and callousness to genocides and pogroms that would foment cataclysmic human suffering and displacement for the next half-century.

While Kissinger has long been vilified for his role in the destruction of Cambodia, his callous response to the 1971 Bangladeshi genocide, where between 200,000-300,000 Bengalis, most of whom were Hindu, were killed and where up to 400,000 Hindu women were raped after imams, aligned with West Pakistan, declared them “war booty,” has long been overlooked.

Nearly 10 million people, mostly Hindus, fled as a result of the monthlong campaign by Pakistan to crush Bengali dissent and eliminate Hindus and secular Muslims.

Gary Bass, who wrote “The Blood Telegram,” a book about American diplomat Archer Blood’s unsuccessful attempts to intervene in stopping Pakistan from committing the genocide, noted that Kissinger not only refused to intervene, but he also downplayed and even joked about the pogrom and Pakistani President Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan’s coordination of the massacres.

Bass noted that, in recounting the role the Pakistani president played in helping him get into China, Kissinger quipped: “Yahya hasn’t had such fun since the last Hindu massacre!”

President Richard Nixon, right, meets with Pakistani President Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan at the White House on Oct. 25, 1970. (Photo by Oliver F. Atkins/NARA/Creative Commons)

Kissinger’s promotion of Pakistan as a key ally was the cost of doing business in South Asia, where the Nixon administration saw supporting Khan’s military rule in East Pakistan as an essential counterweight to Soviet influence in the region, particularly in Hindu-majority India.

But the genocide not only created an influx of Hindu refugees in India, the U.S. government’s unwillingness to declare it a genocide — even after Richard Nixon left office in disgrace and Kissinger’s term as secretary of state ended — also made it a footnote both in modern South Asian history and in Kissinger’s career.

Most Americans are to this day unaware of the sheer destruction of the Hindu population in Bangladesh in just one bloody March in 1971.

Bangladesh’s ruling Awami League ultimately held a number of those who organized the murders and rapes responsible in 2013 — including death sentences for some of the surviving leaders of the genocide. But some Western journalists noted there was little coverage in comparison to the scale of the violence and trauma. Journalist Philip Hensher wrote that the erasure of the genocide enabled by Kissinger was furthered by “the shocking degrees of denial among partisan polemicists and manipulative historians.”

Human remains and war materials from the 1971 Bangladesh Genocide on display at the Liberation War Museum in Dhaka, Bangladesh. (Photo by Adam Jones/Wikipedia/Creative Commons)

While many Bangladeshis do remember the genocide and blame Kissinger for recreating a partition-type mass trauma, it’s imperative that remembering Kissinger’s legacy includes bringing the atrocities he helped create back to the forefront.

The Bangladeshi Hindu population will never return to its pre-1971 level, but giving the genocide proper recognition as one — and Kissinger’s complicity in it — might begin the process of making its victims visible. That alone would add another shovel of dirt to the myth and coffin of realpolitik.

(Murali Balaji is a journalist and a lecturer at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. His books include “Digital Hinduism” and “The Professor and the Pupil,” a political biography of W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)