(The Conversation) — The Bible’s Book of Job opens on an ordinary day in the land of Uz, where a man carefully performs religious rituals to protect his children. This routine has never failed Job, who is described as the most righteous person on the planet. But on this particular day, every one of his children is killed when a powerful wind brings down their house.

This makes no sense! Job did nothing wrong. Three friends visit Job and mourn with him. But an epic debate erupts when they claim that, if Job is the target of God’s wrath, it must have been deserved.

Job, on the other hand, says God has deprived him of justice and demands an explanation from the Almighty. He and his friends argue through poetry – a “rap battle” with beautiful imagery, eloquent wordplay and sarcastic insults.

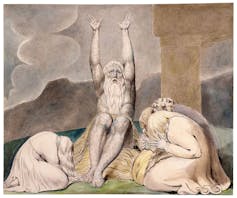

Job mourns with his wife and friends.

William Blake/The Morgan Library via Wikimedia Commons

The Book of Job is frequently touted as a literary masterpiece for the way it challenges foundational beliefs. Many stories have been written about characters like Job, thrust into a topsy-turvy world where nothing works the way it should. Suddenly, they must rethink their understanding about how the universe operates.

As a scholar of the Hebrew Bible, I see the closest parallels in another classic book – but perhaps not one you’d expect.

Down the rabbit hole

Lewis Carroll’s “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,” published in 1865, is a hallmark of children’s literature because of the way it encourages curiosity. Like the Book of Job, the novel upends literary conventions and mocks elders, teachers and religious leaders – really, anyone who tries to tell you that life will be OK if you stop asking questions and follow the rules.

It opens with a little girl named Alice, who is bored one afternoon until she sees a rabbit check its pocket watch and declare that it’s running late. She follows it down a rabbit hole and into Wonderland, a dreamlike place where cats vanish into thin air, babies turn into pigs and caterpillars smoke hookah.

Catching sight of the white rabbit is just the start of Alice’s unnerving adventures.

John Tenniel/The British Library via Wikimedia Commons

Everyday logic no longer applies. Like Job, Alice must question her assumptions if she is to make sense of what is happening around her. Other fantasy worlds require swords, but Alice battles the fantastical creatures of Wonderland with words. As with Job, her ordinary day has gone upside-down, and she finds herself in a debate about reality.

Method to the madness?

Each of these books pushes back against easy answers and heavy-handed morals, which were expected in both ancient wisdom literature and Victorian children’s stories.

Proverbs in Job’s day taught that wickedness leads to punishment. Bestsellers in Carroll’s day included the “Fatal Effects of Disobedience to Parents,” a story about a little girl who burned herself to the ground after her parents told her not to play with fire.

The characters who debate Job and Alice are desperate to find these kinds of lessons in the midst of chaos.

Job’s friends claim that “upright” people never suffer and always enjoy divine protection – unaware that God has already acknowledged Job is “upright.” They look silly as they search in vain for a sin that explains Job’s suffering and scoff when he suggests there is none.

Job’s friends torment him about what he could have done to deserve such ruin.

William Blake/Lithoderm/Wikimedia Commons

Alice, meanwhile, squares up against characters such as the Duchess, who offers ridiculous suggestions about the moral of Alice’s story. The Duchess scoffs when Alice suggests that there is none.

Wordplay, not swordplay

Job and Alice, on the other hand, make fun of society’s rules – as when they sing parodies of religious songs.

Psalm 8, a hymn of praise in the Bible, waxes eloquent about how beautiful it is that the almighty God spends time caring about insignificant humans. Job recites his own version, which complains that it is petty for an infinite creator to spend so much time testing humans.

Carroll grew up singing songs like “Against Idleness and Mischief,” composed by minister Isaac Watts to teach children that they should work hard like an innocent, busy bee. When Alice tries to remember this song, it comes out in Wonderland logic, where a sinister crocodile eats little fish.

Both parodies sarcastically question the underlying assumptions of the original poem. Is it always good to have God’s attention? Is hard work always good?

This shows how both books play with style, including intentional misspellings, rare and even made-up words, and elements borrowed from other languages. They coined enduring phrases such as Job’s “by the skin of my teeth” and “the root of the matter,” or Wonderland’s “down the rabbit hole.”

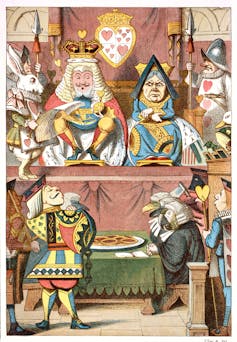

The King and Queen of Hearts preside over an absurd trial in Wonderland.

John Tenniel/The British Library via Wikimedia Commons

These techniques add an otherworldly texture to the language of Uz and Wonderland, far from the books’ original readership in Israel and England. The diction opens countless possibilities for puns and wordplay and forces readers to question basic assumptions about language.

Order in the court

Ultimately, these stories make readers consider a fundamental desire: justice. The adventures of Alice and Job both culminate in epic trials, dominated by stormy authority figures. But if the protagonists can’t even rely on words’ meanings, how can they rely on the law?

When Alice meets Wonderland’s ruler, the Queen of Hearts, she is “frowning like a thunderstorm,” and Alice is “too much frightened to say a word.”

But she is displeased with the queen’s arbitrary distribution of justice and summons the courage to challenge her during a trial for the Knave of Hearts, who stands accused of stealing the sovereign’s tarts.

Throughout the trial, Alice becomes more and more bold. While everyone else cowers in fear, she is willing to question court conventions when they are manipulated by those in power.

Voicing her protest seems to awaken her from Wonderland and back to the “real” world. The book ends with a note about how she will never lose “the simple and loving heart of her childhood” – that is, she won’t forget that kids can have fun for fun’s sake.

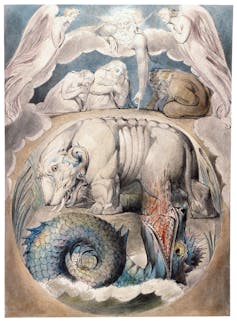

God storms into the conversation.

William Blake/The Morgan Library via Wikimedia Commons

Back in the land of Uz, Job wishes that a court judge would compel God to explain why he is being punished. Certain he did nothing wrong, he says he would wear the accusations like a crown and refute every charge.

God, aware of Job’s innocence the entire time, was never trying to punish him. The deity finally appears in the middle of a whirlwind, and Job puts his hand over his own mouth. It is difficult to argue with the Almighty.

Job had accused his friends of merely flattering God when they insisted his “punishment” was the result of divine wisdom. In the end, God blesses Job for speaking honestly – using a Hebrew word, “nekhonah,” that appears only one other time in the Bible, where it stands in contrast to flattery.

It turns out that God is pleased by those who are honest when a moral agenda doesn’t fit reality – people who, like Job and Alice, speak truth to power.

(Ryan M. Armstrong, Visiting Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, Oklahoma State University. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

![]()