(RNS) — For centuries, Ukraine was home to one of the largest Jewish communities in the world, but never before had the Haggadah, the Passover liturgy that millions of Jews will read around their Seder tables next week, been translated into Ukrainian.

Just in time for this year’s holiday, however, an initial print run of 1,000 copies of “For Our Freedom,” a haggadah in Ukrainian, has been produced by Project Kesher, an American Jewish nonprofit devoted to empowering Jewish women worldwide.

“This has become part of our identity as Ukrainian Jews,” Michal Stamova, the Haggadah’s translator, told Religion News Service. “It’s not only a translation; it’s our life. It’s our culture for the last many years and all of our memories: how we celebrated our first Seders when we were students, all the memories that we remember from our parents who were Jews during the Soviet Union, when baking matzo was forbidden.”

Why a Haggadah in Ukraine’s national language is only now going into print after hundreds of years of Jewish life and three decades of Ukrainian independence has to do with the particular history of the country’s Jewish community.

A century ago, most Ukrainian Jews spoke Yiddish, the Judeo-German language that Ashkenazi Jews brought with them as they migrated into Eastern Europe in the 16th century. Over the course of the 20th century, Soviet Russification policies and ultimately the Holocaust decimated Yiddish culture in Ukraine. Under the Soviet Union, too, Ukrainian was a minority language while Russian was the main language of the state — making it the more natural choice to adopt.

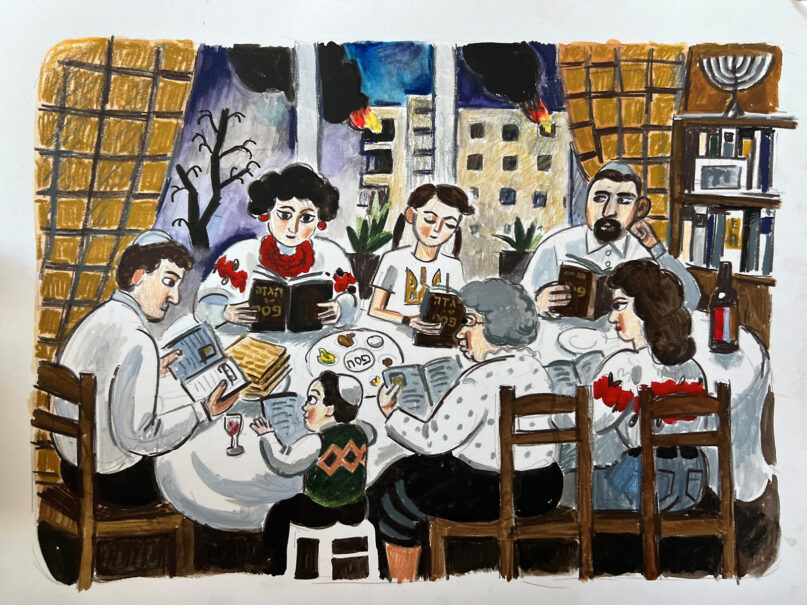

An illustration by Kyiv-born artist Zoya Cherkassky-Nnadi in “For Our Freedom,” a new haggadah in Ukrainian produced by Project Kesher. (Image courtesy of Project Kesher)

In Ukraine, many Jewish communities are found in the eastern parts of the country, or in cities such as Dnipro and Odesa, all areas that have long been majority Russian-speaking, whereas Ukrainian has always been stronger in the country’s west. Even when independence came in the 1990s, these Ukrainian Jews stuck with Russian as their main language.

Even as new borders were sprung up, the Russian language had the advantage of binding Ukrainian Jews to Jewish communities across the former USSR, and even in Israel, where more than 2 million Russian-speaking Jews live, and the United States, where there are another half a million Jewish immigrants and their descendants from the various former Soviet republics.

Thirty years after the fall of the Soviet Union, such communities are still often referred to simply as “Soviet Jews” in the U.S. and Israel.

“Ukrainian Jews always spoke Russian. That really was the norm,” Karyn Gershon, executive director of Project Kesher, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency last year.

Nor were they the only ones. Ukraine as a whole has long been a multilingual society, and even members of Ukraine’s Parliament struggle to speak Ukrainian over Russian. But Russia’s invasions in 2014 and 2022 left many wishing for a cultural and linguistic identity divorced from Russia.

There is also a generational divide, Vladislav Davidzon, a Ukrainian Jewish scholar and author of “Jewish-Ukrainian Relations and the Birth of a Political Nation,” told RNS.

Vladislav Davidzon. (Courtesy photo)

“I do know Ukrainian Jews switched entirely to Ukrainian from Russian, but the older generation still prefers to speak Russian because it’s more comfortable,” Davidzon said. “Ukrainians are speaking Ukrainian more, but it’s happening more slowly than the (Ukrainian) narrative would have you believe.”

Finally, the importation of Jewish liturgy into Ukrainian has been slowed by the fact that most rabbis in Ukraine are Americans or Israeli-born emissaries who came to the country after the fall of the Soviet Union, overwhelmingly members of the Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidic movement.

“The story of Ukrainian Jewry is that their rabbis are not Ukrainians,” Davidzon explained, and they were already struggling to adapt to Russian. They saw little reason to switch to Ukrainian.

But now that is beginning to change, as Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has sparked a change in attitudes across the region.

“There’s a couple of rabbis who, after speaking to their people for 30 years in Russian, are now learning Ukrainian,” Davidzon said. “The younger Jews, they want to pray in Ukrainian, to get the (weekly Torah portion) in Ukrainian.” The rabbis, he said, “are really having to catch up and improve their Ukrainian if they hadn’t already.”

In recent years, Chabad has sponsored translations of the Psalms and daily prayers into Ukrainian.

Still, it took a non-Orthodox backer such as Kesher and the efforts of Stamova, a musicologist who grew up in a Russian-speaking home and was educated in Conservative Jewish institutions, to bring the Haggadah into Ukrainian.

Like many modern Haggadahs, it includes special passages for readers to discuss and contemplate during the Seder, along with the ancient text. Stamova and her colleagues chose ones related to notable Ukrainian Jews, from Vladimir Jabotinsky, an early Zionist soldier and scholar, to Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the current president of Ukraine.

An aerial view of Bakhmut, the site of the heaviest battles with Russian troops in the Donetsk region, Ukraine, June 22, 2023. (AP Photo/Libkos)

It also includes special prayers for the Ukrainian army, as well as prayers for peace. Other passages relate the traditional rituals of Passover to the life most Ukrainians have experienced after more than two years of war.

One of the early motions of the Seder is the dipping of karpas — spring greens — into salt water representing the tears of Jews in Egypt, but also the agricultural bounty normally harvested around the time of Passover. After two years of Russian attacks on Europe’s breadbasket, the idea of a bounteous harvest may be hard to imagine for many in Ukraine. “How can we imagine a green spring in Ukraine right now because of this war?” Stomova asked.

So on the page for karpas, Stamova made sure to include images related to Ukraine’s agricultural strength.

Translating second-century Hebrew and Aramaic text of the Haggadah into modern Ukrainian was no simple task. The difficulties began as early as the first letter of the word Haggadah. The Cyrillic letter that Ukrainian pronounces as an H is pronounced as G in Russian, and Stamova was worried that Ukrainian Jews who still come from Russian-speaking backgrounds would instinctively read it as “Gagadah.” Delving into the richly layered songs and poetry that make up the rest of the Haggadah, things would only get more complex.

But she said the work is an important step in establishing a forward-looking Ukrainian Jewish identity as the Soviet era fades into memory. “It is a symbol of how we’ve manifested as Ukrainian Jews, that we are something different, not just Soviet Jews anymore,” Stamova added.