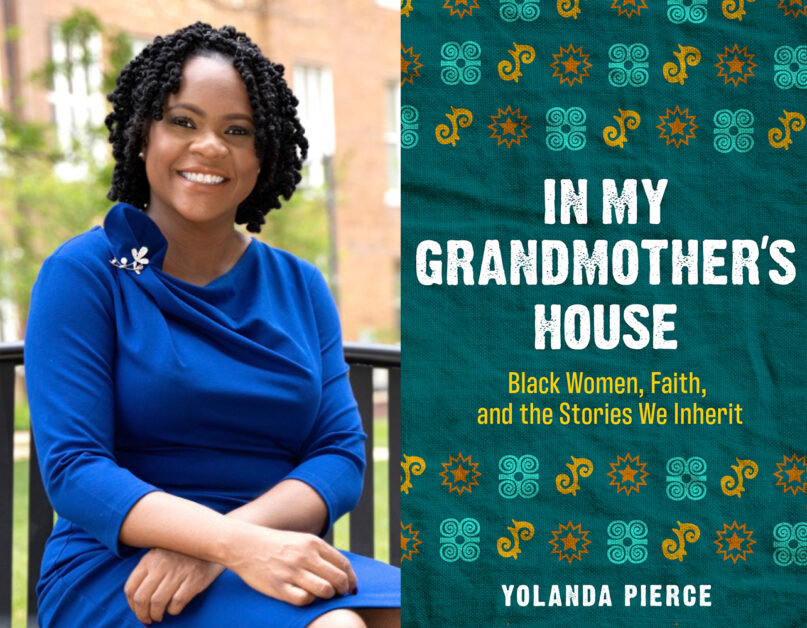

(RNS) — Dean Yolanda Pierce of Howard University School of Divinity has been shaped by, and now teaches, womanist theology, the study of religion through the lens of gender, race and class.

The first woman to lead the predominantly Black theological school in its 150-year history has written a book chronicling how that theology stretches back generations before the term was used.

“In My Grandmother’s House: Black Women, Faith, and the Stories We Inherit” was released Tuesday (Feb. 16).

“If the only theology we have is (Martin) Luther or (John) Calvin, then we’re missing how God moves in a world for a group of people who don’t know Luther or Calvin, will never read (their) work nor are interested in the 1500s in which they lived,” she said. “So I’m really trying to shift the discourse about who can do theology and what counts as theological source material.”

RELATED: Beyoncé Mass replaces hymns with ‘Survivor’ and ‘Flaws and All’

Pierce, who is in her 40s and identifies as a Pentecostal, talked with Religion News Service about what she learned from her grandmother, the kinds of hymns she doesn’t sing and her expectations about the future of the Black church.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

In the preface of your book, you described “grandmother theology” as “a subset of womanist theology.” Please explain the connection between the two.

I’m using the terminology “grandmother theology” to refer to the generations prior to our parents. It is to refer to the grandmothers, aunties, the other mothers, the nonbiological connections women have and to really expand the category of womanist theology, so the words and the thoughts of grandmothers and church mothers and other mothers are a part of the conversation.

Can you define “womanist theology” for the average person who may not use it much?

Womanist theology was created in the ’60s and ’70s to address the fact that much of the theology being done in the academy excluded communities of color, and then much of early Black theology excluded the voices of women. Womanist theology was birthed by Black women who wanted to see themselves, the concerns of their communities, addressed within the theological discourse. With Black women making up the majority and sometimes as much as 80, 90% of the church, it felt like such a shame the theology wasn’t reflecting the experiences of the people who are its most faithful witnesses.

Even with that kind of power of women you speak of in your book, you also describe women — especially at your grandmother’s Brooklyn, New York, church — maintaining some of the patriarchal traditions of the church as you grew up, including modest dress. What did you learn from that tension?

I grew up in a tradition where women covered their head in order to be able to enter the sanctuary. They really believed these actions — dressing modestly, living a very modest life, living a very holy life — were absolutely essential to their salvation, to how they understood who God was. And so, for me, it has been a challenge to tear apart the question of legalism from the question of holiness, to maintain the beauty of holiness but for it not to be caught up in the legalism of patriarchy.

You described how your grandparents displayed a picture depicting Jesus as a Black man and how the coloring book someone gave you as a child on an Easter Sunday that had a white Jesus on the cover disappeared before you got home from church. How did these decisions about the color of Jesus shape you?

My grandparents, who were from the rural South, they really had an understanding of Jesus as Black. And as a theologian, I talk about Black Jesus to talk about a Christ, a Messiah, who is on the underside of history, who cares about the least of these. I talk about Black Jesus in order to interrupt the notion that Jesus comes from Europe, but instead really is birthed in the Afro-Asiatic cradle. I never until I was an adult saw images of white Jesus. And It’s only as an adult I appreciated that what they were trying to give me was a sense of the divine — who looked like me and could love me, a little brown girl — who was not outside of my family tree, but was a part of my own spiritual lineage.

Also as an adult, you said you no longer sing hymns with words like “washed me white as snow.” Why did you take that step?

I no longer can sing hymns that attempt to, even metaphorically, strip me of my Blackness. I don’t have to be washed white as snow in order to be presentable before God. I can be wonderful and beautiful in my Blackness. I don’t have to be stripped of the very ethnic and cultural identity, which God gave me, in order to be presentable before God.

You said as an adult you had attended a multiracial, multiethnic congregation for several years but realized it could not be your spiritual home. How do you compare your departure from it to reports of Black Americans who have left multiracial churches in recent years, sometimes over political differences?

There may, in fact, be some people who are called to multiracial, multiethnic churches, but I now know I’m not one of them. I think the idea of it sounds good, but the practice of it falls far short. In many of these multiracial and multiethnic churches, you still have an ethos of white supremacy, even though there might be lots of different faces in the pews. Many people of color find themselves in those places, and they’re still dealing with racism. They’re still dealing with white supremacy. They’re still dealing with white nationalist theology. And so, as recent studies have indicated, many African Americans are leaving these multiracial churches. That’s a political decision. That’s a personal decision. But for me, it is a spiritual decision. I’m not going to be any place that does not feel like sanctuary.

Besides womanist theology, you speak of Mariology, the theology concerning the mother of Jesus. What does Mariology say to Black women in particular?

I have a high Mariology. I love the story of Mary. I think about the many ways in which Black people, Black men and women, are raising children under institutional violence but are still trying to build within them a love of God, a love of church, a love for tradition and culture. The story of Mary resonates for me — the story of how this mother witnesses her child killed. It was state-sanctioned violence. He was martyred. He was lynched. That crucifixion tree is a lynching tree.

You critique the Black church for restrictions on women from the pulpit and ignoring abuse. But you express some hope for the next generation of believers even as there are reports that millennials attend church, including the Black church, less often than their elders. If you find hope in the future of the Black church, where do you find it?

The hope may not be in the building. I think that because we were very busy building the institutional Black church for all kinds of important reasons, we placed a lot of emphasis on the church house, the building itself. I think my hope for the Black church is not connected to the buildings, not even connected to whether, after this pandemic, people return back to the churches. But my hope is in watching generations of people who really take seriously justice, who really connect justice and faith, who want to live out this command of walking humbly and loving and doing justice, the command in Micah 6:8. They really see justice and equity at the heart of their belief system. And I’m hopeful, because I think the Black church has always been an artistic movement, and so, where there is music and song and dance, those are elements of the Black church, and they can live outside of the doors of the church.

RELATED: Black women cracking ‘stained-glass ceilings’ with Jesus’ 7 last words