(RNS) — R. Scott Okamoto still believed in Jesus the first time he strode onto the campus of Azusa Pacific University, an evangelical Christian school in Southern California, for a job interview in 1998. Fifteen years later, he left without a job or his faith.

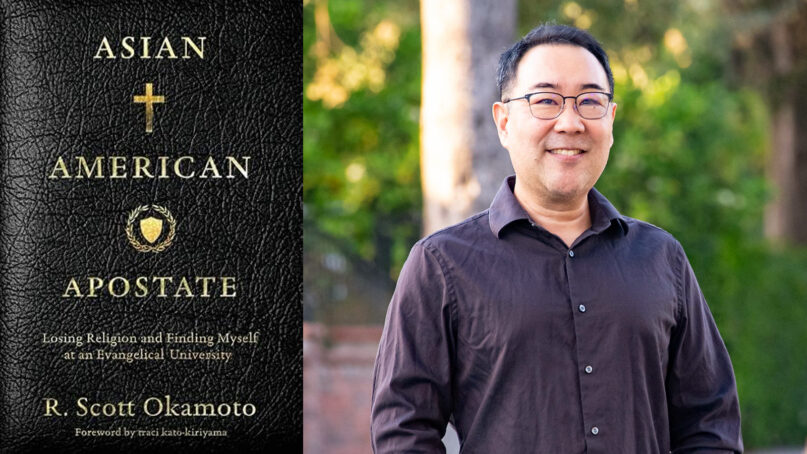

But in his debut book, “Asian American Apostate: Losing Religion and Finding Myself at an Evangelical University,” Okamoto explains that his experience granted him more clarity and sanity about religion and Christianity in particular than he had enjoyed before. “Asian American Apostate” is an inside look at the mosh of underground LGBTQ groups, right-wing Christian beliefs and the unlikely alliances operating on campus in the decades before the Trump era.

Okamoto’s scathing critique is also an account of how enduring a white-centric culture allowed him to become a “self-actualized Japanese American.”

Religion News Service spoke to musician and podcaster Okamoto about the book. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you continue to teach at an evangelical university after you’d lost your faith?

Ninety-nine percent of what I was doing was teaching English at the university level. The last 1 or 2% was what they call faith integration. I felt very qualified to do that because even as I was losing my faith, I was still integrating their faith into what we were studying. I felt good about helping students who were very fundamentalist evangelical broaden their understanding of their faith, the same way I had, and I saw a lot of myself in them. It was just tough on me because I had to grin and bear the horrible things that were said.

I also really wanted to support the Asian American/Pacific Islander population that was invisible and very marginalized. And there was an LGBTQIA underground club. They had no institutional support, and they knew they could be kicked out if they were caught. I was deeply involved with them. So I had a lot of reasons to stay, even though I wanted to leave at the end of every year. It was taxing on my soul.

You write that your time there in the early 2000s gave you “a front row seat to the coming of the era of Trump.”

Christians worship Donald Trump because he’s wealthy. If he wasn’t a billionaire, they wouldn’t listen to him, but they believe God has blessed him. Tied to that is this attitude of hatred for people who are different from them. There was a real shift between the end of that happy “born again” phase of the late 1990s and the rise of Fox News. My students would come to class ready to crucify anyone different than them, especially gay people or people of color. At first, there were just a few students here and there, then (campus) clubs started to push this xenophobic, racist narrative.

Students would try to argue that Saddam Hussein was responsible for 9/11. The most popular argument I remember was that taking prayer out of schools in the 1960s led to all the bad things that happened since. When I would point out bad things did happen before the ’60s, it didn’t matter. They weren’t looking for conversation.

So when I hear Tucker Carlson, and everyone’s shocked, my view is that he’s just building on what has already been built up in evangelical culture.

You chose not to name the university in the book. Why?

The last thing I wanted was for this book to be a hit piece on APU. It could be any evangelical school. The academic world is not compatible with evangelical culture. They say it is, and they want it to be, but they don’t want to teach Shakespeare, they don’t believe in science. They have to get stacks of exemptions from Title IX just to get their accreditation.

At some point, you have to ask, what’s the point? If you want to be a university, be a university, the way the Catholics do. They hire all manner of professors and accept all students. Evangelicals say the professors have to believe all the same things, but they don’t really mean it. Students are supposed to go to chapel and sign a statement of faith, but they’ll bring in football players from big schools and won’t make them go to chapel. They want all the appearances and perhaps privileges of being an excellent academic institution, while winking and nodding to the evangelical culture, saying, “Really this is just an indoctrination center to send out good Christian kids with a degree.”

You say the emergence of the gay-straight alliance forced you to choose a path you’d previously had the privilege to avoid.

The school had a kind of don’t ask, don’t tell policy, as long as people weren’t being overtly in support of gay students — because, let’s be real, there were no discussions about trans or nonbinary students during this time. I could point students in the direction of resources outside of Azusa Pacific. Obviously, it wasn’t enough. It’s pretty sad when the only ally you can find is a cis het English professor who didn’t decry homosexuality as a mortal sin. So when the kids decided they wanted to make an underground group, they approached me to be their sort of unofficial faculty adviser.

I sat and cried with so many students who whose parents or friends had disowned them because they’d come out. It definitely meant exposing myself to higher scrutiny from the school, but it was bigger than whatever career I was trying to forge. I had a place of privilege because my wife made more money than me. I was ready to help them.

The events you write about took place more than a decade ago. Why write about them now?

When I first started writing everything down, back in maybe 2010, it was just therapy for me. I thought, the world needs to see the truth about evangelicals, but I didn’t want to write a book that was just negative, because I had seen so much positivity both inside and outside of APU. I hope what comes through in the book is the concept of building bridges between people who don’t agree. I’m still in touch with dozens of students, some of whom made huge strides in their development as human beings to be more caring, more open and accepting. That only happens through, I think, relationships. I wanted to shine light on the problems of the school, but also offer some kind of hope.

Who were you writing this book for, and what takeaways do you hope they have?

I am not really writing this for evangelicals. I wrote the book for anyone who’s intellectually curious about an inside look to this culture. My story has a lot of identity issues that a lot of us deal with in America. Finding our people is a universal problem. But I’m definitely writing for the people who are getting out of faith or are sitting in their churches thinking, “This is toxic, this is problematic.” There is a way out.