(RNS) — As a kid growing up in rural Wisconsin, writer and food historian Christina Ward attended tent revivals even though she and her family weren’t practicing Christians.

“The local preacher would pick up all the farm kids and take them, kids only, so all the parents and grandparents wanted their kids to go,” she recalled. “It didn’t matter what you were actually practicing.”

While free child care may have been a highlight for those parents and grandparents, Ward and other kids found a different appeal: They’d get an ice cream sundae every time they correctly learned a Bible verse.

“I think that really started this connection for me, that, you know, religion equals food,” Ward said.

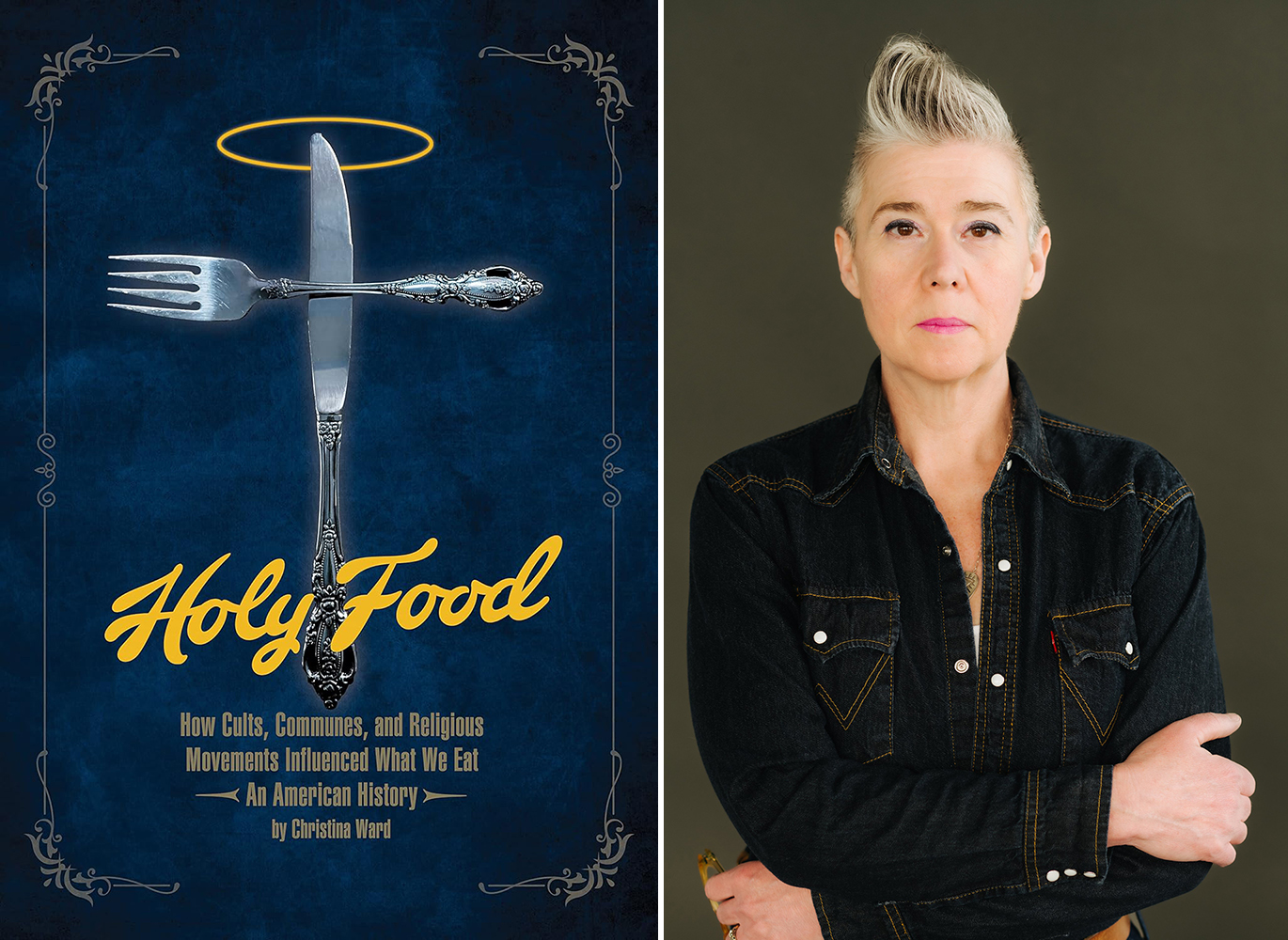

That lifelong fascination and five years of research culminate in Ward’s new book, “Holy Food: How Cults, Communes, and Religious Movements Influenced What We Eat.”

“Holy Food: How Cults, Communes, and Religious Movements Influenced What We Eat” and author Christina Ward. Courtesy images

“You start seeing a lot of different interpretations of all scripture,” Ward said about the religious and cultural landscape at the time. “A lot of times revelations have a lot to do with a food because they morph into these ideas of tribal identification and who we are, how we recognize each other.”

The book is divided into chapters that delve into the nuances of different time periods and belief systems, with recipes at the end. It features recipes from the Oneida Community, Seventh-day Adventists, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Christian mystics, Nation of Islam, The Source Family, The Satanic Temple and many more, each with their own contribution to religion and American food culture.

The recipes were tested by Ward and a small community of friends during the beginning of the pandemic. They’re kept authentic to the time with only a few modern updates; for example, instructions on making homemade tofu are omitted because tofu is much more readily available.

Ward, with a self-proclaimed sweet tooth, says she enjoyed making and eating the desserts most.

“My favorite recipe is the early German version of Trauben Pastete, which is a grape pie,” she said. “It’s done a lot in the Midwestern region, where we have fox grapes and Concord grapes, but it also comes from a western New York tradition. Very good for fall.” The recipe is from the Amana Colony, affiliated with Pietism and the Anabaptist tradition.

Another favorite of hers is the Hare Krishna version of coconut burfi, taken from an International Society for Krishna Consciousness cookbook.

“Holy Food” contains plenty more recipes for those with a similar sweet tooth: molasses cookies from the Rappites, raw vegan caramel dip from the Black Israelite group Israel United in Christ and Mother Ann’s birthday cake from the Shakers.

Women with a Mormon charity group prepare foods in September 1937. Photo by Hansel Mieth/The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

It also features savory dishes and main courses, from 3HO’s Golden Temple sandwich to famous LDS funeral potatoes.

Plenty of these recipes are more obscure, but just as many remain prevalent in the U.S. today even if their origins are less well-known.

“Our local co-op last month had their sandwich special — it was the sandwich from the Golden Temple cookbook that was published in the mid-’70s. I was blown away. I asked them about it, and they eventually told me they used to use all these cookbooks,” Ward said.

This speaks to an interconnectedness among religious groups and with broader culture that Ward says is “only possible in America: based on our tax laws, our business culture, First Amendment and so on.”

Visitors to the Oneida Community eat strawberry shortcake outdoors in Oneida, N.Y., circa 1880. Courtesy of the Oneida Community Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries

She notes how McDonald’s Filet-O-Fish was created by a Catholic franchise owner in Cincinnati who wasn’t selling many burgers on Fridays because of the practice of some Christian groups to abstain from meat on that day. Ward is based out of Milwaukee, a heavily Catholic area, and having a fish fry on Fridays is fundamental for the same reason.

“I would wager that a lot of folks don’t even know that it’s rooted in Catholic culture,” Ward said.

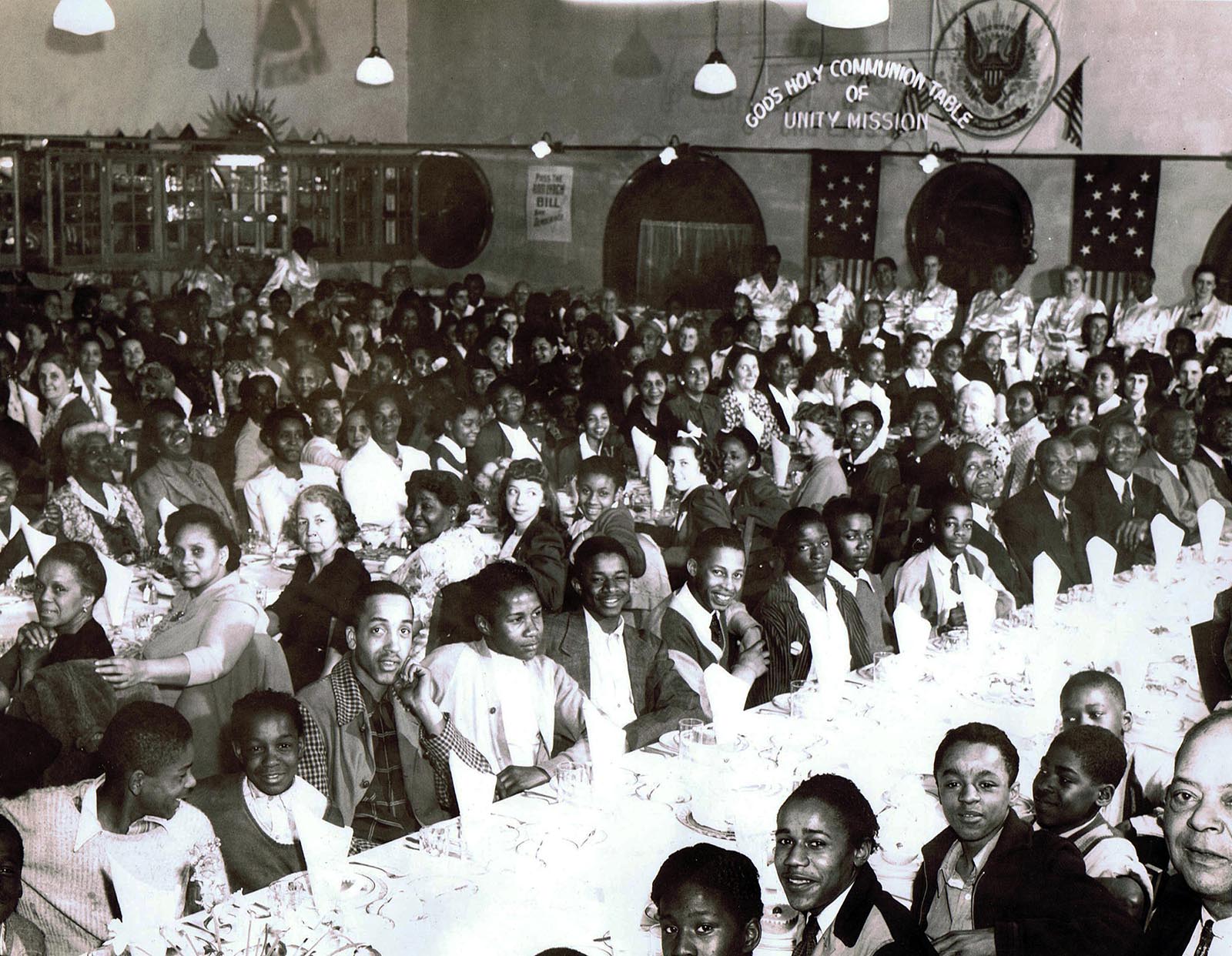

Used both as a way to bring people together and, in more harmful cases, to control, food is a fundamental part of religion, and religion plays a fundamental role in how food is prepared and eaten, maintains Ward.

It also often comes down to something as personal as tastes and preference. The nuances are endless, and it’s these complex relationships and trends that “Holy Food” explores hands (and mouth) on.

“I love how these traditions are often very rooted to the people in the place where they grew,” Ward said. “For me, history is in the rabbit holes. It’s always about people.”

Father Divine’s Peace Mission communion dinner, circa 1940. (Getty Images)