(RNS) — Last week, the Rev. Raymond de Souza, the Catholic priest and conservative commentator, argued in a Wall Street Journal column titled “Do Catholics Need Questions? No, Answers” that the church is devoting too much time and energy to asking questions. The solution to the issues facing the modern church, he said, is to treat spiritual matters with certainty.

“Questions deserve answers. The Gospel provides them. The church is to preach them,” de Souza wrote.

The occasion for de Souza’s column was a gathering in Rome last month where nearly 500 cardinals, bishops, priests, nuns and Catholic laypeople, at the behest of Pope Francis, wrestled with a spate of controversial theological questions: Should priests be allowed to marry? Should women be allowed to become deacons? And what should we do with all of these LGBTQ Catholics who keep stubbornly populating the pews?

The conversations were the heart of the Synod on Synodality, a three-year process of theological discussion that began with a survey of people in churches and dioceses in 2021 and will conclude with another gathering in Rome next fall.

RELATED: In Vatican summit’s closing document, agreement that synodality is church’s future

Many voices in the church have welcomed the chance to address such consequential questions and applaud the slow, intentional process of communal discernment. Conservative Catholics, on the other hand, see the synod as further proof that, in de Souza’s words, “confidence and clarity have dissipated in Rome in recent years,” and say the church should be in the business of providing answers rather than asking questions.

As Cardinal Timothy Dolan told de Souza, “No man will give his life for a question mark; he will for an exclamation point.”

Pope Francis, sitting at right, participates in the opening session of the 16th General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops in the Paul VI Hall at the Vatican, Oct. 4, 2023. Pope Francis convened a global gathering of bishops and laypeople to discuss the future of the Catholic Church, including some hot-button issues that have previously been considered off the table for discussion. Key agenda items included women’s role in the church, welcoming LGBTQ+ Catholics and how bishops exercise authority. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

As a Protestant, I have no stake in this family feud. But like some of my Roman Catholic cousins, I’m concerned by the notion that theological questions are to be avoided, much less feared. The Christian tradition has historically held that questions are holy, curiosity is sacred, discernment is wisdom and doubting is a necessary component, without which faith itself is impossible.

Bible scholars note that Jesus asked more than 300 questions in the New Testament, and was asked 187. He answered only three. Jesus’ teachings were frequently cryptic, as he often spoke in parables — stories that invite investigation, discussion and discernment. To build one’s faith on answer-giving rather than question-asking is to depart from the pattern modeled by the first cause of Christian faith itself.

Jesus was drawing on Judaism’s long tradition centering questions in the life of faith. In Hebrew Scripture, questions are one of the primary ways that God forges and nurtures relationships with humans, who frequently return the favor. Job wrestles with a litany of questions before God famously fails to answers them. The Psalmist asks dozens of questions, whether lamenting or praising. Modern Judaism has continued this tradition — using rituals such as Passover to teach children that “to be Jewish is to ask questions” — but some modern Christians have abandoned it for a more sure-footed kind of faith.

The scary thing about questions, of course, is that you never know where they will take you. When you ask big, theological questions such as the ones that Catholics are asking right now the Spirit just might lead you to a conclusion you did not expect. New conclusions often call us to the uncomfortable work of change — to let go, to grow, to find new ways of living in the world. Which is why I suspect Jesus loved them so much, and why religious leaders often resist them.

If spiritual questions involve risk, religious communities that shut them down present the greater danger. David Dark, author of “The Sacredness of Questioning Everything,” points out, “When religion won’t tolerate questions, objections, or differences of opinion and all it can do is threaten excommunication, violence, and hellfire, it has an unfortunate habit of producing some of the most hateful people to ever walk the earth.”

Historically, it is not spiritual mystics and philosophers who have perpetrated social evils, but religious fundamentalists and ideologues. That’s why, Dark says, criticism of religion must be part of religion. Faithfulness is only possible when the faithful are allowed to critique, complain, reform, challenge, investigate and question.

As Blaise Pascal said, people never do evil so completely as when they do it cheerfully from religious conviction.

Growing up a Southern Baptist, I was trained in something called “apologetics,” which is not the art of saying you’re sorry, but rather the discipline of making logical defenses for our belief system. The great depths of God and faith were boiled down to arguments small enough to fit on an index card, which made them easy to deploy in debates. Our job was not to investigate the answers we were given, but to merely memorize them. In an answer-obsessed religious tradition like mine, asking pesky doctrinal questions is considered a sign of spiritual weakness. So my faith was full of exclamation points and very few question marks.

The moment I gained a little autonomy I granted myself permission to ask all of the taboo questions that were too scandalous to speak aloud in childhood. Should we read the Bible literally? And is modern science really anti-faith? And do Republican political positions really reflect so-called Christian values?

Contrary to what I’d been told, these questions did not lead me to some secular or atheistic wasteland. They led me to a deeper and richer faithfulness, a place where the Spirit could stir and speak in new ways. My stagnant and combative faith became dynamic and curious.

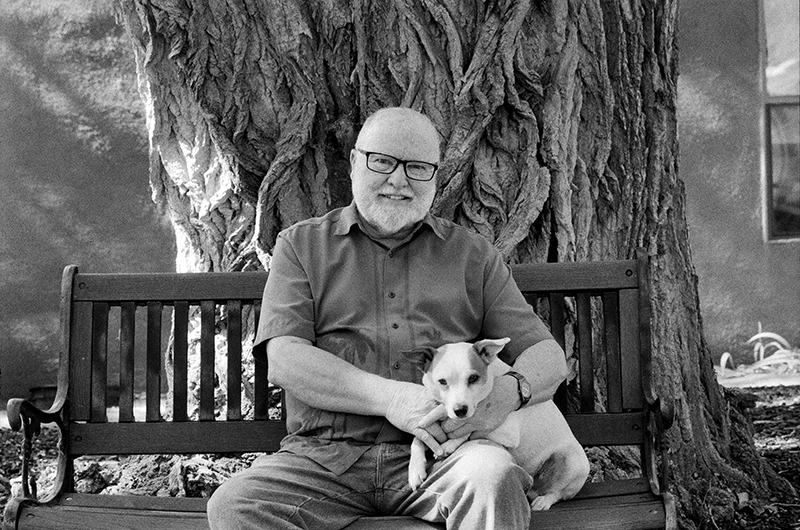

Richard Rohr in 2019. (Photo by Daniel Epstein)

Perhaps ironically, a key transformation in my spiritual life came as a result of reading the writings of a Catholic priest, the Franciscan mystic Richard Rohr. He notes that answer-focused religiosity is powerfully attractive because it appeals to the ego, which seeks to control and possess. It allows “us to be arrogant, falsely self-assured, and closed down as a person.” Or in the phrasing of the Apostle Paul, “Knowledge puffs up.”

According to Rohr, true faith is connected not to the ego but to the human spirit, which is more concerned with discovering the right questions than possessing the right answers. “A discerning and inquiring spirit will make us a discoverer in touch with our deeper unconscious and the deeper truth,” Rohr writes, “whereas a glib ‘I have the answers’ spirit makes us into a protected boundary of cliches.”

RELATED: Vatican synod is ‘not about ideology,’ participants say

This does not mean that people of faith have nothing to offer the world but an endless train of questions. Rather it means being mindful that “for now, we see through a glass, darkly” and that we should hold our conclusions loosely and with deep humility. It means being willing to do the hard work of asking, seeking and knocking on doors, which is not just the work of a synod, but the work of a lifetime. Faith cannot live by answers alone, but by the questions that lead us continually back to our sacred Scriptures and the heart of God.

In 1903, a military academy cadet mailed some of his poems to the Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke, asking for an honest assessment. Instead of providing a valuation of the young man’s poetry, Rilke responded over the next five years with 10 letters offering wise reflections about how to live well in this befuddling world. One of the recurrent themes in Rilke’s correspondence, later compiled and published as “Letters to a Young Poet,” is the need to cultivate a lifelong practice of courageous questioning:

I would like to beg you, dear Sir, as well as I can, to have patience with everything unresolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves as if they were locked rooms or books written in a very foreign language. Do not now search for the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.

Roman Catholic or Protestant, you could do worse than following this advice: Remember the pattern set for us by the ever-curious Christ. Allow yourself the freedom to wonder and wander. Let go of any childish certainties and embrace childlike curiosity. Consider the ways that a living God may be doing something new among you — yes, even now. And patiently live the sacred questions you’re asking in hope that you may one day live into a more holy answer.